Fibre isn’t a single food but a component of all plants that we humans can’t digest or absorb in the small intestine. It passes through our small intestine undigested but once it arrives to the colon, our microbes, living in this part of our gut, take care of it. They ferment the fiber and some compounds resulting from the fermentation are used by the host (the human). One way to put it is that fiber is food for our colonic microbiota and their “waste” is food for us. This close is our relationship.

Fiber can be divided into soluble and insoluble

The term dietary fiber includes many specific types of fiber. Because this group is so heterogeneous, there are different ways to classify fibers. One widely used classification separates fiber into soluble and insoluble, depending on whether they can be dispersed in water or not.

Insoluble fiber passes through our intestinal tract withoug being utilized by us and only partialy by our microbiota. This does not mean it isn’t beneficial for us. In fact, it serves a good purpose: it helps waste transit through the colon faster, which diminishes the time that toxins in that waste are in contact with our colonic cells. This is very important, as those toxins have the potential to cause colon cancer. The least time they are in contact with our cells, the lowest the risk of developing colon cancer.

Soluble fiber is the one we cannot digest but our microbes can. To be clear, not all of them do. Only some groups of bacteria can ferment soluble fiber, so it is important to have these families in our microbial community in order to benefit from the products of this fermentation.

What foods are rich in fiber?

The answer is all plant based foods. Good food sources of a mixture of dietary fibers are:

- beans and legumes

- nuts

- seeds

- whole grains

- cereals

- fruits

- vegetables

Oat products and legumes are rich sources of soluble and viscous fiber. Wheat bran and whole grains are rich sources of insoluble and nonviscous fiber.

The following table gives examples of specific foods in each category and their content in fiber:

| Beans and legumes | gr/cup | Nuts and seeds | gr/cup | Whole grains and cereals | gr/cup | Fruits and vegetables | gr/cup |

| Navy beans (cooked, boiled) | 19.1 | Almonds | 17.9 | Oats | 16.5 | Raspberries (raw) | 8.0 |

| Split peas (cooked, boiled) | 16.3 | Walnuts | 8.5 | Quinoa (cooked) | 5.2 | Blackberries (raw) | 7.6 |

| Lentils (cooked, boiled) | 15.6 | Pecans | 10.5 | Barley (pearled, cooked) | 6.0 | Figs (raw) | 1.9 (1 unit) |

| Chickpeas (cooked, boiled) | 12.5 | Cashew nuts (oil roasted) | 4.3 | Rice (Brown, médium grain, cooked) | 3.5 | Avocados (raw) | 10.1 (1 cup cubes) |

| Kidney beans (cooked, boiled) | 11.3 | Chestnuts (roasted) | 7.3 | Rice flour (Brown) | 7.3 | Pears (asian, raw) | 4.4 (1 unit) |

| Broadbeans (cooked, boiled) | 9.2 | Hazelnuts | 11.2 | Bulgur (cooked) | 8.2 | Apples (raw, with skin) | 3.0 (1 cup chopped) |

| Lima beans (cooked, boiled) | 13.2 | Chia seeds | 9.8 | Buckwheat | 17.0 | Artichokes (cooked, boiled, drained) | 6.8 (1 unit) |

| Mung beans (cooked, boiled) | 15.4 | Flax seeds | 2.8 (1 tbsp) | Millet (cooked) | 2.3 | Peas (green, cooked, boiled, drained) | 8.8 |

| Mungo beans (cooked, boiled) | 11.5 | Pumpkin and squash seeds (whole, roasted) | 11.8 | Rye flour (dark) | 30.5 | Brussels sprouts (raw) | 3.3 |

| Hummus (home prepared) | 0.6 (1 tbsp) | Sunflower seeds (oil roasted) | 14.3 | Sorghum flour (whole grain) | 8.0 | Spinach (cooked, boiled, drained) | 4.3 |

Content of fiber in gr/cup. When the measure of one cup does not apply, the alternative measure is specified in brackets. Fiber content depends on several characteristics, for example whether the food is raw or cooked. For more detailed information and a large database of specific foods visit USDA National Nutrient Database. Tbsp: tablespoon.

Health benefits of fiber

Consumption of fiber in the diet has beneficial effects in our bodies:

- reduces bad cholesterol in blood

- lowers blood sugar and improves insulin responses

- regulates bowel movements, by softening and adding bulk to stool and reducing transit time through the colon

This physiological effects of fiber may prevent diseases. For instance, many studies have provided consistent evidence that high fiber intake helps with weight management and also helps prevent cardiovascular disease and type 2 diabetes.

Feeding the gut microbiota

Dietary fiber has a great impact in our gut microbiota: it affects the microbiota’s composition and metabolism.

As I said earlier, fiber feeds microbes in the gut but not all the fiber-fermenting microbes feed on the same type of fiber. So, while some types of fiber will induce growth of some groups of bacteria, other fibers will do the same with different bacteria. This is one of the reasons for including a variety of fibers in our diets. Variety means more different types of bacteria growing in our guts. And a more diverse gut microbiota means better health for us. Moreover, bacteria that can feed on fiber will produce metabolites that feed other bacteria that cannot ferment fiber. This is called cross-feeding and is an indirect mechanism by which fiber supports a diverse microbiota.

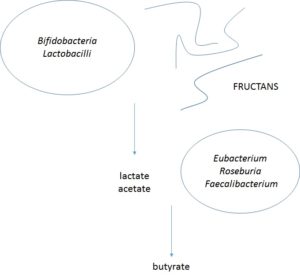

For instance, Bifidobacteria and lactobacilli ferment fructans (a specific type of fiber) and, as a result, produce lactate and acetate. Then Eubacterium, Roseburia, and Faecalibacterium utilize lactate and acetate to produce butyrate.

Lactate, acetate and butyrate are short chain fatty acids (SCFAs) produced when bacteria ferment fiber. On top of these three, other SCFAs are propionate, formate and caproate. In fact, the main products of microbes fermenting fiber are acetate, butyrate and propionate. Butyrate is the most studied SCFA and it has been shown that has a protective effect against colorectal cancer.

More about butyrate in the epigenetics section.